NEW FILM REMEMBERS THOSE WHO EVADED CAPTURE AFTER THE RAID

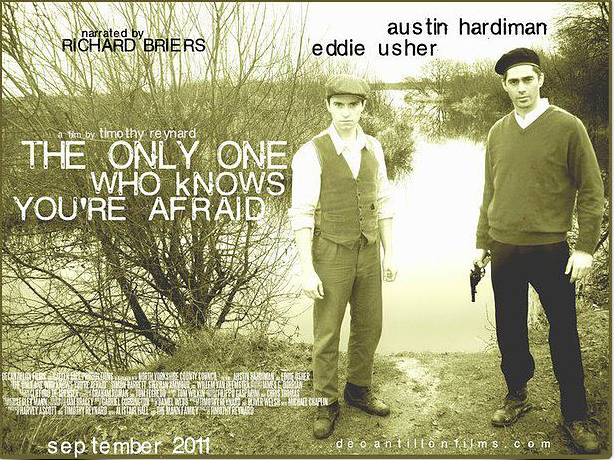

Where does all the time go? Hard to believe I'm so late in passing on news of a premiere I attended, in Harrogate, back on September 6th. On show, for the first time and to a black-tie gathering, was a new film by talented young director Tim Reynard (https://www.decantillonfilms.com/theonlyone). Entitled 'The Only One Who Knows You're Afraid', the film tells the story of two Commandos taken under the protection of French civilians during the first phase of an escape odyssey that would eventually see them returned to the UK via Gibraltar. The film excels in exploring the all-too-easily forgotten risks ordinary - well, perhaps not so ordinary - people took in concealing and aiding Allied combatants whose discovery would lead to a concentration camp, or even execution.

The film was introduced by a prologue written by myself, and voiced wonderfully by Richard Briers - text below. There was also a rather insipid speech by a silver-haired gent.....no - hold on, that was me too. Just goes to show that if you know you have to give a speech DO NOT attend a full-on wedding in Ireland immediately before and then travel back to the UK by Stenna Lineski (well, to us it felt like crossing the Baltic on a Soviet ferry back in the '50s).

Tim and his writing partner Olly were present in Saint-Nazaire during the March commemoration, and got to tour poor old Campbeltown. They attended the cross-laying at the cemetery in La Baule/Escoublac and were able to meet the veterans Bill 'Tiger' Watson, and General Corran Purdon, who every year without fail presage the main ceremony at the Chariot memorial with a private period of contemplation by the beautifully-tended gravesides of their fallen comrades.

Full details of the film, its cast and crew plus a 'teaser' video can be seen at the above De Cantillon Films web address. The evasion portrayed was based on the successful 'home-runs' of Corporal George Wheeler, MM, and Lance-Corporal Robert Sims, also MM. The total number to make it home without first having been captured was five, the others being Lance-Corporal Arnie Howarth (sheltered in his German-occupied school by Principal, M. Etienne Baratte), Lance-Corporal Douglas, and Private Harding.

A huge amount of effort went into this film: and for me it was both refreshing and inspiring to work with people so young and yet so intent on paying due tribute to events now almost lost in the mists of time.

PROLOGUE

It’s just after one o’clock on the morning

of the 28th. It’s cold. It’s pitch black. You’re crouched on the

deck of a boat, almost within sight of the coast of Occupied France. You can’t

see it yet; but for the first time in days you can smell the smells of land: of

seaweed on the unseen shore; of fields and trees and human habitation –odours

almost alien after two long days sailing through the Channel and the Bay of

Biscay.

The proximity of land has brought the first

stabs of real fear, and you wonder if the other Commandos in your small party

are feeling it too. Not so much fear of the enemy you know lies waiting, but of

letting yourself down, or still worse the mates you’ve been living and training

with forever – or so it sometimes seemed.

They’re all around you, your mates, their

battledress damp from the ever-present drizzle, their faces dark beneath the

dull steel of their helmets. Everyone’s weapons are at the ready, with packs

full of explosive charges and pouches stuffed with ammo and grenades. Aside

from muffled orders to the sailors at the forward and after Oerlikon cannons,

the only noise to be heard is of the boat’s own powerful engines, a roar so

loud they must surely hear it in Paris.

Just before you’d left Falmouth, they’d finally mentioned all the guns that were going to be waiting for you in the

estuary of the River Loire. You’d never heard of Saint-Nazaire in your life

before: now you can’t divorce its name from thoughts of the mighty defences put

in place to defend it. A lot of U-Boats lived there, just like the one your

escorting destroyers had put under yesterday. Silly bugger to show himself

anyway: must’ve imagined no British ships would dare be seen where we were.

Hard to tear your eyes away from the land

and all those unseen guns. How many of them are even now pointed directly at you? How will you react the second they

open up? You twist around, and search the darkness for the rest of the fleet.

Up ahead, that darker patch, that must be Campbeltown, with tons of high explosive packed in her bow. Somebody’s going to get a nasty surprise. Trailing on either side of the old

destroyer, feathers of phosphorescence breaking from their bows, are the

remaining 17 ships – built of wood, just like your own. To aid in

identification each bears a number painted in white – just like pleasure boats

on a Blackpool pond. Maybe there won’t be any firing. Maybe the enemy’ll just

get megaphones and call out from the shore, “Come in number so and so: your

time is up…”. Bloody tinderboxes. Even after 400 miles of sailing, each of them

still had 2,000 gallons of petrol in its tanks. Whose bloody stupid idea was

that! Some Royal Navy if that’s all they can afford to give a person. At least Campbeltown, rusting relic though she might be, was built from good old steel.

It’s suddenly harder to breathe; harder to

take your mind off the fuses, detonators and plastic explosives filling the

pack you’re going to be lugging ashore – a pack which, now it’s a target, seems

to have grown to twice its former size. Another stab of fear, this time almost

crippling as the brilliant, ice-cold pencil of a searchlight sweeps across the

waves, only just missing the last boats’ wakes. As it goes out, there’s a loud

metallic clicking next to you as one of your Protection Party cocks his Tommy

gun. Nerves stretched so tight you could probably play a tune on them. A drink

would be good, just about now…..

Your officer appears out of the gloom. It’s

the Navy’s job to defend the boat, but with nothing but those tiny Oerlikons

against the whole might of the enemy, they’ll need all the help you ‘brown

Jobs’ can give them. Orders are to be ready at a second’s notice – but

absolutely not to fire until the klaxon sounds.

There’s something going on up ahead. You

don’t know it, but the Navy are exchanging stolen signals with the Germans,

hoping they’ll accept the fleet of strange ships as their own. Can the Jerries really be that stupid? You’ve been told they believe

the port to be impregnable. Complacency on their part was to be the fleet’s

trump card. The British would never dare come here – ergo the British can’t be

here – ergo the ships must be German: simple.

A half-seen shadow passes by on your port

quarter. It’s the buoy that marks the entrance to the narrowest part of the

estuary. Any closer to the shore and the German guns crews’ll be able to toss

their bloody shells at you.

Flashes up ahead now; coming from the

shore. Flashes first, then the thud of heavy guns heard only microseconds

before first Campbeltown’s klaxon, then all the

klaxons on the following boats, shriek out the signal to return fire. The

sudden hammering of an Oerlikon cannon only feet away from your ears stuns your

senses momentarily; then the Commandos’ Tommy guns and Brens join in. So

pretty, and yet so deadly, all those streams of coloured tracer reaching out

from boat and shore. Then you wonder what a time it is for somebody to be down

below, banging on the hull with a hammer - until the sickening realization

dawns that these are the sounds of enemy fire tearing through the boat’s thin

mahogany skin.

You feel helpless. As a demolition expert,

all you can afford to carry in addition to your

weighty pack, is an American Colt pistol. May as well chuck it at the shore for

all the good it’ll do. So you make yourself small, very small, and you pray.

And maybe you think how long it seems now since you and your mates were

swanning round Scotland, taking full advantage of the effect your Commando

flash had on all the girls. And not just the girls –sometimes their mothers

too….

A muffled choke, and the Oerlikon gunner is

hit, slumping dead in his sling. A flurry of activity as he is quickly replaced

- and the dreadful racket of the gun begins all over again.

A wall looms on the port beam: a

lighthouse, then an enemy gun on top of some building, firing over your head at

the starboard column. It’s the outer harbour already. Only few hundred yards to

go and you’ll be ashore on the soil of France. No passport control on this trip…!

Your officer gets the various parties

sorted out – Protection in front, Demolition behind, while the crew begin to

pull down the side stanchions. Stand up – at least as high as you dare: pack

on: my God it’s like slinging a bag of cement. Ahead are the silhouettes of the

twin pill-boxes that defend the Old Mole, the landing point for all the boats

in your column. You wonder if anybody’s made it: then you find your answer in

the gush of flame that suddenly engulfs the boat just in front of yours. Poor

bastards. What a way to go.

Your own boats heels sharply to port as it

breasts the lighthouse at the end of the Mole. For a brief moment you catch a

glimpse of Campbeltown, the old girl lit up like

a Christmas tree, shell after shell crashing into her sides. She must be almost

there. Going fast as hell, from the size of her bow wave. It’s a sight you’ll

remember as long as you live – as long as you live! Bloody Germans won’t know what hit them.

Amidst the dreadful racket and the roar of

flames, you can still make out the tinkling of broken glass falling from the

shattered lantern room, now directly above the boat. The streams of tracer from

the Mole guns can no longer depress enough to hold you as a target, so your

boat slides easily beneath them, engines revving, and comes to a stop alongside

the slipway on the structure’s eastern face. More thuds; this time from grenades

tossed down from its upper surface and landing on the deck where you’d just been. Lucky, that. A bark of orders and you’re off, stumbling

over the bodies of the forward gun crew. There’s seaweed on the slipway: you

stumble. Can’t fall over or you’ll be helpless as an upturned turtle. A rattle

of Tommy gun fire up ahead and then you’re off the Mole, heading for the

shelter of the dockside buildings and the deepest, darkest shadow you can find.

Ahead of you, empty as a Scotsman’s wallet

after a night out in Glasgow, lies the broad square that separates the Old Town

tenements opposite, from the sprawl of silent dockyard buildings to your rear.

You can still see the estuary – but you might have wished you couldn’t: for a

rippling horizon of flame and smoke seems to be all that now remains of all

your comfy, floating billets.

A staccato metallic clatter and a long

spray of bullets shreds a metal waste can at the edge of the square. The

Germans must’ve put machine-guns in the tenements’ upper windows. Beneath the

shattered can, your Protection party officer lies sprawled, like he was still

on a firing range, his Tommy gun kicking as he seeks them out. Fat chance. He

only looks about eighteen. They say he wants to be a doctor: maybe should’ve

stuck to that – instead of this.

It’s all going pear-shaped. The square you

have to cross to get to your target looks about as inviting as a shark’s smile.

Your own officer tries to pick his way across – but soon collapses to the

ground, dead, like as not. Nobody’s getting across there now. No way ahead. No

way back - not now all the boats have gone. Outnumbered twenty to one. But are

we downhearted? No, we’re bloody not. We’re Commandos chum – and we’ll do the

job and get back home one way or another. Just like we always do……

-

A total of 264 Commandos sailed to

Saint-Nazaire to knock out that port’s giant dry dock. Their aim was to keep

the German battleship Tirpitz away from the

lumbering convoys by destroying the only bolt-hole on the Atlantic seabord

large enough to house her should she ever be damaged in battle. A faint hope

indeed: but then, these were desperate times.

The Commandos were split into three groups,

each with its complement of heavily laden demolition experts. 78 men were to

storm ashore from HMS Campbeltown, once the old girl had buried her

explosive-filled bow in the dock’s outer gate. 84 Men, plus a small

headquarters party were to land from small boats, right behind her in the Old

Entrance. A similar number were to come ashore at the Old Mole.

It had all looked so good on paper. But

like all plans it had fallen apart the second the first shot was fired. Campbeltown, strongest ship in the fleet, did all that was asked of her: but

the small boats were cut to pieces - and the men aboard them. Of six boats

meant to land Commandos at the Old Entrance, only one succeeded – a story

repeated exactly at the Old Mole. Handfuls of Commandos were left to fight

where whole teams should have engaged the enemy. They could have surrendered –

nobody would have thought ill of them. But these were exceptional individuals,

trained to win out where others could not. Gibraltar lay 1,000 miles away. In

the way was Occupied France and half the German Army.

(Copyright, J Dorrian, 2011)

(Copyright, J Dorrian, 2011)

Comments